Diversity and inclusion: eight steps to move beyond good intentions

Diversity and inclusion are no longer self-evident. Public debates have become sharper, resistance is more visible, and organizations are more cautious. That calls for more deliberate choices, greater attention to buy-in, and stronger anchoring in leadership, systems, and communication. With that lens, I now revisit these steps. The underlying principles remain the same, but I have added an eighth step. Applying them today requires greater awareness and sharper judgment.

TL;DR – in short

Diversity and inclusion have become both more important and more complex. Good intentions are not enough. Inclusion only exists when people genuinely feel at home. That requires awareness of unconscious exclusion, listening to lived experiences, visible role modeling by leaders, adjustments to systems, space for differences, and thoughtful communication.

What’s new is step 8: sustaining inclusion and making it part of everyday work. Only then does diversity stop being a project or campaign and become a lasting choice.

Why are diversity and inclusion important?

People who do not feel at home in an organization, or who fear being excluded, feel less comfortable, are less engaged, and perform less well. An inclusive organization functions better because it creates room for different perspectives and insights. That is why inclusive thinking and action matter.

In practice, however, this often proves more difficult than expected. Most organizations have good intentions, but those intentions do not automatically lead to an inclusive work environment.

How can organizations ensure that inclusion is actually experienced?

For years, the police force faced heavy criticism for its lack of diversity. The desire was often expressed that the police should better reflect society. Yet for a long time, this proved difficult. Partly because people from certain target groups did not apply, but also because those who did often did not feel at home. More recently, progress has been made—precisely by paying attention not only to diversity, but also to inclusion.

What do we mean by diversity and inclusion?

Diversity and inclusion are often mentioned in the same breath, but they are not the same. Inclusion is about the open, respectful culture an organization aims to create: a culture in which everyone can be themselves. Diversity focuses on building a workforce that is diverse in composition.

Both are essential. Diversity without inclusion leads to turnover. Inclusion without diversity often remains limited to good intentions.

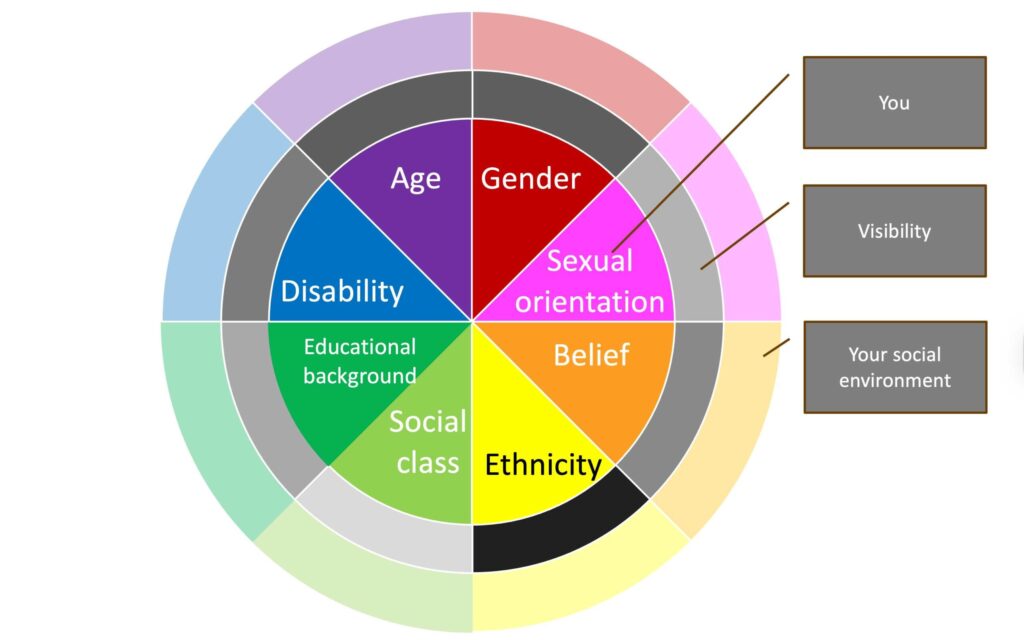

The diversity circle

Figure 1. Different dimensions of diversity

Diversity can refer to many dimensions. It is often associated with gender or ethnicity, but it also includes sexual orientation, religion or belief, social class, education, physical or mental disability, age, and generation.

To better understand diversity within and around an organization, the diversity circle can be helpful. It distinguishes between how you define yourself (the core of the circle), how visible that dimension is to others, and how most people in your immediate environment define themselves. Whether someone feels at home is not only about identity, but also about context. The more mixed a group is, the more natural interaction becomes. That also requires attention to how people address one another.

The eight steps

The biggest challenge in diversity and inclusion is that many people do not realize they are excluding others. Almost everyone will say they do not discriminate. Yet unconscious processes play a major role.

One key mechanism is the in-group–out-group effect. We naturally feel more connected to people who resemble us. We understand them better. People who are “different” are more quickly placed in the out-group—a group we understand less and are also less inclined to understand (as described by Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow).

Step 1. Check your self-image—and that of the organization

Inclusion policy therefore starts with holding up a mirror. How open is the organization really? How diverse is the workforce? And what behaviors do we show—often unconsciously—toward people who do not belong to the dominant group?

Comments meant as jokes can still exclude. Calling a colleague “typically overly sensitive” or “effeminate” may seem harmless, but it does not contribute to equality.

Awareness is the starting point. The biggest issue is often that people do not see their unconscious behavior. And when they do, it is frequently downplayed. Only when people become aware of their behavior and its impact does room for change emerge. This can be encouraged through an internal quiz with recognizable examples or an inclusion checklist.

Interestingly, being smart does not automatically make people more inclusive. On the contrary, managers who are used to being right are often better at rationalizing their assumptions. That is why training and reflection matter, as does daily contact with people who are different from you. That contact increases understanding and reduces stereotyping. The biggest problem with diversity is often that we do not see who is being excluded.

Leaders play a crucial role here. They, too, need to step back regularly and acknowledge that they are not always inclusive in their thinking or actions. Many leaders operate in relatively homogeneous environments without realizing it. When a prime minister once said he was looking for “the best candidate,” he often meant the best candidate from his familiar circle. That is not ill intent, but it is a pattern, reinforced by group pressure. Leaders need insight into these patterns and tools to act more inclusively. Workshops with HR can help, as can openly addressing seemingly innocent jokes that nevertheless exclude.

Step 2. Listen actively: from assumptions to experiences

Inclusion does not start with broadcasting messages, but with listening. Listening sessions with employees from different groups reveal where policy and practice diverge. What is it like to work here as a woman, an LGBTQ+ employee, a person with a disability, or someone with a bicultural background?

The goal is not to solve everything immediately, but to understand where barriers arise. This also requires something from the organization: the willingness to tolerate discomfort without becoming defensive. Especially in a time of polarized opinions, the ability to listen is a strategic strength.

Step 3. Role modeling diversity and inclusion

Role modeling by leaders remains essential, but it goes beyond symbolism. A CEO who visibly supports inclusion—by joining Pride events, for example—helps. A CEO who also incorporates inclusion into appointments, decision-making, and priorities truly makes the difference. Some governments work with gender-balanced cabinets, and companies like Vattenfall have appointed diversity and inclusion officers at executive level.

At a time when diversity is contested, role modeling also means continuing to stand up for inclusion when it is not popular. Not activism, but consistent leadership.

Step 4. Structures and systems

Much exclusion is not rooted in intentions, but in systems. In meeting times that exclude caregivers. In language that feels natural to some but alien to others. In buildings, IT systems, or HR processes designed for the “average employee.”

An inclusive organization dares to critically examine these systems—not from a place of political correctness, but by asking a simple question: who can function well here, and who cannot?

Consider name westernization. When I worked abroad, I often used my middle name, Tom, because “Huib” was considered difficult. Many people with international names do the same in the Netherlands. It seems convenient, but it is actually undesirable. In an inclusive organization, everyone makes the effort to learn and use each other’s real names. Something as simple as writing names down and practicing pronunciation—slowly, for everyone, even if they are named Anna or John—can make a difference.

Step 5. Don’t clone—broaden your view of talent

Selecting people based on “fit with the organization” sounds logical, but often leads to reproducing sameness. Inclusion requires explicitly valuing difference. That means training selection committees, revisiting criteria, and accepting that someone does not have to resemble you to add value.

Diversity does not happen by accident. You have to consciously make room for it.

Step 6. Space for identity and resilience

Inclusion does not mean everyone has to become the same. It means differences are allowed to exist. Employees need space to organize themselves and share experiences. That helps make exclusion visible and keeps it open for discussion.

In the police force, for example, a leadership think tank called Pharessia—Greek for “speaking freely”—was created for leaders with different ethnic backgrounds. Colleagues can approach them to talk about how they are treated within the organization. Situations of exclusion or discrimination are discussed and addressed there. The network functions both as a support system and as a mirror for the organization.

Many organizations also have LGBTQ+ networks, offering spaces for connection and collective action when needed. In education, this can be seen in Gender & Sexuality Alliances, groups of queer and straight students who work together to address discrimination and exclusion. A well-known example is Coming Out Day, when students wear purple shirts to show solidarity.

These networks contribute to visibility, recognition, and mutual support, while also highlighting gaps between policy and practice.

Building resilience is equally important. Employees in customer-facing roles may encounter discrimination externally as well. I once heard about a technician who rang a customer’s doorbell and was greeted with a racist remark. He was too stunned to respond, but the situation could easily have escalated. Preparing people for such encounters matters.

Step 7. Communication: internal campaigns or not?

Companies organize diversity dinners or activities around Coming Out Day. Communication can strengthen inclusion—but it can also undermine it. Internal campaigns, theme days, and visible symbols only work if they align with employees’ everyday experiences. Without deeper anchoring, they quickly feel like window dressing.

Avoid making inclusion visible only at fixed moments during the year. Inclusion is more than a theme week or a flag. It should also be reflected in imagery, language, and daily communication. Addressing people as “everyone” or “dear colleagues” is just as friendly as “ladies and gentlemen,” and more inclusive.

Equally important is a communication department that is diverse itself. Diversity and inclusion start by holding up a mirror to your own team. You can only communicate inclusively if you are aware of where you stand. That mirror can take many forms: how diverse is the communication team, and how diverse is its thinking?

Good communication helps create meaning, facilitate conversations, and explain choices. Especially now that inclusion is no longer automatically supported, this requires careful, connecting, and strategic communication.

Step 8. Sustain it and make it part of everyday work

Working on diversity and inclusion is not a project with a clear beginning and end. It requires long-term attention, precisely because priorities shift, roles change, and societal developments affect organizations. Without deliberate anchoring, there is a real risk that progress slowly fades into the background.

That is why diversity and inclusion should not be treated as something extra, but as part of everyday work. It should show up in regular processes: team meetings, performance and development conversations, leadership programs, HR cycles, and communication planning. Not as a separate theme, but as a natural point of attention.

Sustaining inclusion also means regularly asking what still works and what needs adjustment. What helped in one phase may need revision later. Teams change, organizations evolve, and societal contexts shift. That requires continuous listening, learning, and course correction.

Organizations that embed inclusion into daily routines make it less dependent on individual champions or temporary momentum. Diversity and inclusion then stop being projects or campaigns and become part of how the organization collaborates, makes decisions, and develops.

In conclusion: work on diversity and inclusion

An inclusive organization is a better place to work and collaborate. Employees feel more connected and engaged. For organizations with a public or societal mission, inclusion also helps them better reflect the society they serve.

Inclusive communication is not a checklist you tick off once. It is a continuous, empathetic process. It requires ongoing listening, learning, and collaboration with representatives of the groups you want to reach. They are best positioned to tell you what works in practice—and what does not. Do not assume too much on their behalf.

Diversity and inclusion are therefore not temporary challenges or moral projects. They are strategic choices that must be woven into everyday work: into how you collaborate, lead, communicate, and make decisions. That takes attention and perseverance—and sometimes the willingness to tolerate tension.

Especially now.

And take a look at this style guide.

Inspired by the seven segments of the diversity circle by Dien Bos

Huib Koeleman